A long time ago in 1979 I got really lucky. In those years you were more likely to get serendipitous when browsing the book stands near Flora Fountain. There were some genuine beauties you could buy easily on a collegian’s pocket money, that is if you saved up instead of the wada pavs and movies. I was obsessed with books and still am but it gets harder each year with the devaluation of the rupee and printing costs and things going through the roof. Also work is getting slicker and more finished, wonderful print values and superlative form but don’t you get the feeling that ‘content’ is sorely lacking. Everything looks like a mass make over. So Arthur Tress comes across even today as enriched uranium.

His early book called The Dream Collector is a documentary, social commentary and artistic rendition of the subliminal, the unconscious, the REM and the John Fowles of the visual world.

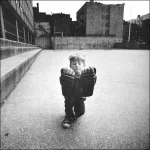

The most wonderful part about Tress and all subsequent work that he has produced is his effortlessness. The Dream Collector is all about children enacting their fantasies, making real the virtual, making surreal the obscure.

Tress goes (because ‘went’ is so past tense and ‘done’) about recording on a tape machine, children’s dreams, believing that dreams are telling us about ourselves, that they are an indicator of what we are concealing, putting aside, not dealing with, in other words dreams are playing out for us a script for action to be taken, the past, present and future becoming one homogenous continuum.

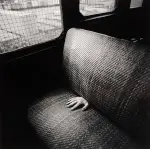

Arthur Tress ‘renders several dominant themes in his photographs, the child’s expression of fear combined with intuitive curiosity his hands reaching, exploring shape and texture; and the emergence from darkness and light’. He gets on amazingly well with children which may account for the ease with which they can relate to him. He has a child like quality that they intuitively understand as genuine.

The foreword talks about the easy conversational, non threatening style that Arthur Tress has that children trust, that he takes them seriously must throw them off. He is never disparaging or dismissive or patronising. He shows them respect and in return they give him a dream for his collection. He then plays the dream back for them and initiates an enactment in a setting and backdrop that will lend itself to the mood and the sentiment. Then he waits patiently for that flash of inspiration when the child does something spontaneous and beguiling and then he knows he’s collected the rare species in a jam jar.

The photographs are rich in photographic skill and temperament. The images are disturbing in large part due to the illusion becoming tonal and bromide. Like Fowles it is unnerving to see dreams like butterflies in a display case impaled on a pin. The ambience is largely desolate and lonely. There are monsters looming out of children’s heads. He employs the diptych in many frame, the top half revealing one reality, the lower half another. If one becomes introspective which is what the book is ultimately seeking, you begin to see yourself as a child might see you, it can be ugly and cause you to stop, think and feel. Each image is a surprise as dreams are generally. Each dream is visually explicit and in black and white. The dreams connect literary to the audio which is connected to the smell to the texture and the sensation, the emotion and the intellect. What dreams are saying are seldom the obvious.

Tress is a versatile photographer a couple of his other books are available with homoerotic overtones and generally the macabre. His exhibition called Fantastic Voyage ran at the Piramal gallery for photography in 1995 and was a treat to behold, there was humour and exquisitely crafted prints. Tress is not as well known as he should be. But look out for his work which is loaded always with surprise and adventure.